zoomacademia.com – The Khmer Rouge, or “Red Khmer,” was a radical communist regime that controlled Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, marking one of the darkest periods in the country’s history. Under the leadership of Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge initiated an extreme socialist revolution that sought to transform Cambodian society into a peasant-dominated agrarian utopia, but in doing so, they orchestrated a massive genocide, leading to the deaths of approximately 1.7 million people—about 21% of the Cambodian population at the time.

The Rise of the Khmer Rouge

The origins of the Khmer Rouge can be traced back to the Cambodian Communist Party in the early 1950s, influenced by both Vietnamese communism and Maoist ideologies from China. Cambodia, then a French colony, gained independence in 1953. However, the country was soon destabilized by the spillover of the Vietnam War, which increased both domestic instability and foreign intervention.

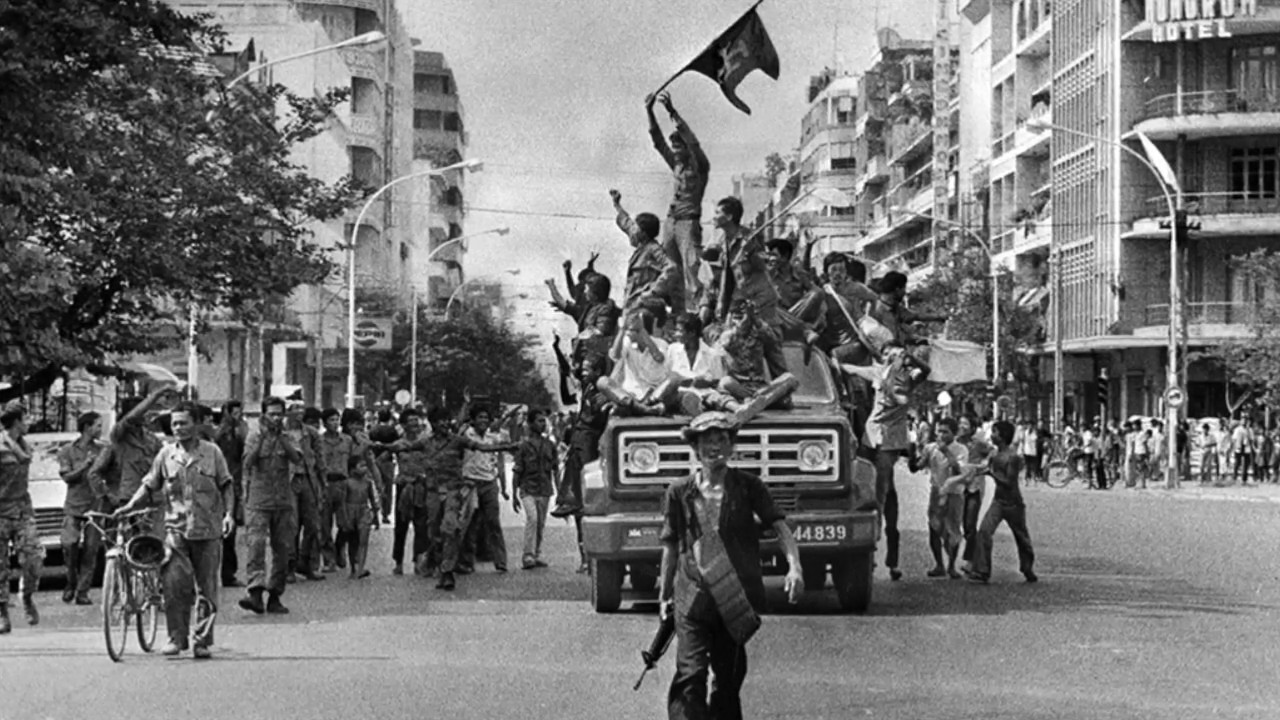

In 1970, a U.S.-backed coup led to the ousting of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who had previously managed a delicate balance of power and maintained a stance of neutrality in the Vietnam conflict. The coup led to the establishment of a pro-American government led by General Lon Nol. This shift allowed the Khmer Rouge, who positioned themselves as defenders of Cambodian nationalism against foreign influence, to gain widespread support, particularly in rural areas. With backing from North Vietnam and China, the Khmer Rouge capitalized on the discontent with the U.S.-backed government, ultimately capturing Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital, on April 17, 1975.

Establishing a Radical Regime

Upon taking control, the Khmer Rouge wasted no time in implementing their vision of a communist utopia. Led by Pol Pot, the regime rebranded Cambodia as “Democratic Kampuchea” and forcibly evacuated cities, including Phnom Penh, moving millions to the countryside to work in labor camps. The Khmer Rouge ideology viewed urban life, education, religion, and anything associated with the modern world as a corrupting influence, so they sought to dismantle all forms of modern society.

The Khmer Rouge’s policies were extremely oppressive. Money, private property, and family structures were abolished, and individuals were forced to work grueling hours under harsh conditions. They believed that complete self-sufficiency would be achieved through agricultural labor, and any failure to meet impossible quotas was met with severe punishment, including death. The regime targeted intellectuals, professionals, and religious leaders, perceiving them as threats. Even wearing glasses could result in execution, as it was seen as a sign of Western-influenced education.

The Genocide and Mass Atrocities

The brutal policies and purges carried out by the Khmer Rouge led to widespread famine, disease, and executions. The notorious Tuol Sleng Prison (S-21), where thousands were tortured and killed, became a symbol of the regime’s brutality. Between 1.5 and 2 million people lost their lives due to starvation, overwork, disease, and systematic executions. Whole families were targeted to prevent future retribution against the regime.

The genocide was characterized by a brutal efficiency aimed at eradicating perceived “enemies” within society. The Khmer Rouge had a particular disdain for ethnic minorities, including the Cham Muslim population, Vietnamese, and Chinese Cambodians, as well as for Buddhist monks, whom they systematically targeted for elimination.

Fall of the Khmer Rouge

By the end of the 1970s, the Khmer Rouge regime had weakened Cambodia, creating tensions with Vietnam, who had long been involved in Southeast Asia’s political landscape. In December 1978, Vietnamese forces invaded Cambodia, quickly toppling the Khmer Rouge and installing a government led by former Khmer Rouge officials who opposed Pol Pot’s faction. By January 1979, Phnom Penh was liberated, marking the official end of the Khmer Rouge’s brutal reign.

However, the Khmer Rouge continued to operate as a guerrilla force along the Cambodian-Thai border for several years, funded in part by China and by forces opposing Vietnam’s influence in the region. Pol Pot and his remaining followers eluded justice for many years. Pol Pot himself died in 1998, having never faced trial for his actions.

Legacy and the Quest for Justice

In the decades following the Khmer Rouge’s fall, Cambodia has struggled to rebuild from the traumatic legacy of the genocide. The country established the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) in 2006 to prosecute surviving leaders of the Khmer Rouge for war crimes and crimes against humanity. While some leaders, like “Brother Number Two” Nuon Chea, faced justice, the trials were slow, and some perpetrators died before they could be held accountable.

Today, Cambodia continues to grapple with the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge. The country’s cultural, educational, and religious institutions were decimated, and the psychological scars of the genocide remain. Memorials such as the Choeung Ek Killing Fields and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum serve as reminders of the atrocities committed and as places of reflection for the victims and their families.

Conclusion

The history of the Khmer Rouge serves as a cautionary tale of the dangers of extremist ideology and totalitarian rule. While Cambodia has made strides in rebuilding, the shadow of the Khmer Rouge era remains deeply etched in its national identity, influencing Cambodian society, politics, and its quest for justice and remembrance.